Heads or Hands: Hired for What You Know, or What You do?

By Tim Williams

Would you rather be hired for your ability to execute, or your ability to solve? Which is more valuable?

A carpenter is given a blueprint and skillfully begins measuring, cutting, and hammering. The framed building is a valuable work product; the result of carefully following a detailed Scope of Work.

The blueprint is the work of the architect, who applies his sense of design and knowledge of structural engineering to develop a detailed set of plans that can be faithfully executed by craftsmen in the building trade.

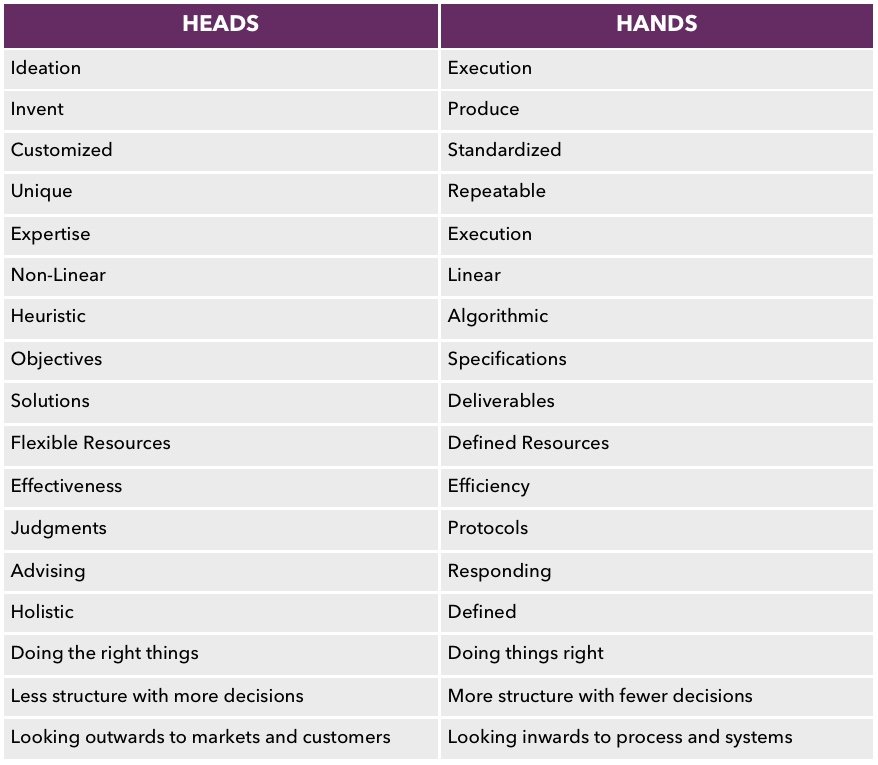

The carpenter does manual work. The architect is engaged in knowledge work. While a proficient carpenter is essential to turning a set of blueprints into an objective reality, the architect deals with the subjective elements of design, appearance, selection of materials, and meeting the objectives of the client.

While both types of work are valuable and necessary (one would be quite useless without the other), they are just the same different skill sets that have different levels of perceived value. In a marketing context, one is a growth driver; the other a service provider.

Upstream vs. Downstream

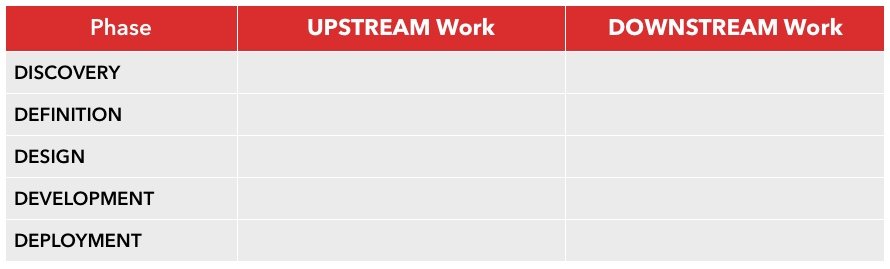

In today’s unbundled marketplace, it’s essential to recognize the difference between “Upstream” and “Downstream” work not only because they require different talent, but also different pricing. Because the talent required to do Downstream work is widely available (think resizing a banner ad), clients are essentially looking for a price that is consistent with other providers.

The fact that today’s agencies derive so much of their revenues from Downstream work (production, implementation) has prompted professional buyers to research and publish “should cost” averages that agencies are expected to match for this type of work. In the mind of the buyer, this class of execution work has a market price, which puts considerable pressure on agencies to develop a low-cost model for Downstream work.

On the other hand, Upstream work is much harder to categorize and publish in a cost database. What’s the value of a big idea, a brilliant concept, or a game-changing strategy? Procurement types will nonetheless attempt to categorize this class of high-value work, in part because that’s the buyer’s job: to turn various service offerings into apples-to-apples comparisons.

The job of the seller (that’s you) is to consciously and continually identify and separate different classes of value, and sell, price, and deliver them accordingly.

By definition, knowledge work involves invention and innovation. In the agency arsenal, it is — or should be — your equivalent of a Black Box offering. Both the inputs and the outputs are qualitative and non-linear. This type of work, when done well, is difficult to duplicate and hard to compare.

For this reason, when we’re hired as “heads,” this work should be priced based on the perceived value to the customer. The price should be based on “marginal utility” (perceived usefulness), whereas “hands” work can be priced based on “marginal cost.”

While a rate card is completely inappropriate for Black Box work, it’s an acceptable pricing approach for White Box work. It’s not worth the time and effort to develop custom pricing for routine production work. Sophisticated clients already have clear expectations of what these types of tasks should cost, so many agencies are now developing a menu of these services with unit pricing indicated. This is not an hourly rate, but rather a fixed price for a specific task or deliverable.

There’s an exceptionally competitive market for Downstream work, so it’s essential that you avoid these three mistakes:

Assigning Upstream talent to Downstream work (you can’t afford to do that)

Combining Upstream and Downstream work in a “blended rate” (which makes the Downstream work too expensive and the Upstream work not expensive enough)

Counting on Downstream work to make your margins (there’s too much pricing pressure on this class of work; instead price your Upstream work profitably)

Deconstructing Your Offering

Remember that the essential job of professionally-trained buyers is to attempt to commoditize the seller’s offerings, develop “should cost” averages, and frame services as though they all have equal value.

Don’t be fooled or confused into accepting this procurement tactic as an objective reality. Deconstruct your offerings into different classes of value and present and sell them accordingly. An effective way to do this is to think through the major phases of a project or assignment and assign the various services, functions or deliverables (the items that would normally appear on an invoice) to either the Upstream column or the Downstream column. Do this for each major type of project that would be typical for your business model.

When a talented agency transforms the global reputation of a brand through a brilliant marketing program based on unique customer insights, that’s an example of the kind of high-value problem solving professional firms get hired for in the first place. It’s the kind of “magic” that characterizes knowledge work, creative thinking, and professional expertise.

But an outstanding idea requires outstanding execution. Great buildings are a result not only of great architects but great builders. Both are good and valuable skills sets. Just remember that they’re valuable in different ways to the people who buy your services.